AY-SKHUHL- CHAPTER TWO - (ROUGH DRAFT - PART A)

In which dirt-poor wogs come to terms with the cost of living large, native animals are swiftly slaughtered on balconies, uniforms are bought to be stretched across playgrounds, and my ancestors are disgraced both in terms of construction and physical worthlessness.

After the seedy village-like confines of Glebe, Woollarah was a revelation to me. Certainly in terms of flashy housing and lack of Serbian-speaking neighbours.

My family had gone from being property owners to itinerant renters, my father had lost his beloved garage, every friend I had made in primary school may well have been on another planet, the tortoise I had as a pet was gone, and the rabbit I also had as pet had been turned into goulash the week before we moved. I’m sure my father would have eaten the tortoise too, but he couldn’t get the thing out from under the kitchen lino where it had crawled after escaping from its enclosure during the packing process. And my safe and leafy backyard was now, apparently, the street.

But none of that really mattered. What mattered was that mum would no longer have to live in the house were her mum had died. And we were all hopeful that her tears would finally stop, she would start to get over her loss, and we would not have to spend every weekend at Rookwood cemetery; my parents tending my grandmother’s grave and me doing really crap Parkour over the nearby Chinese graves. It had been a most difficult year for my family.

And the vast unknown of high school now loomed before me.

Still, as I looked out the floor-to-ceiling window of my new bedroom and admired the lights of Bellevue Hill in the valley below me (we were on the seventh floor of a twelve-floor block of quite roomy flats), I could not help but grin when I beheld the communal swimming pool that awaited me below.

So, taking a positive outlook, we now had a pool, my wonderfully engaging aunt lived in the same block of flats, and we had a hell of a view.

Oh, and we also now had possums. Well, we only had them briefly. On the second night after we had moved in, I had shit myself, yelping my terror at a massive black shape sitting on my balcony railing. My father had run in to my room, beheld the beast, ran back out, then ran back in and killed it with a single blow from a big concreting shovel. We didn’t have possums any more after that. Unfortunately the brutalised carcass had somehow fallen onto the balcony of the flat below, and there were some words exchanged between my father and the fellow living there that very evening. Our under-neighbour, Mr Steiner, who had been feeding the local possums for years, was quite horrified to suddenly find Chester’s slaughtered corpse on his bedroom balcony, and came straight upstairs to ask my father what had happened to the possum.

My father’s English, while not great, was certainly up to the task of being interrogated by our slightly-built neighbour, who was simply breathless with the horror of Chester’s demise.

He ummed and panted at my father’s impassive mien as he explained Chester was a frequent and dearly loved visitor to these flats, and along with his possum friends, Mitzy, Golda, Solomon, and Sam, greatly enjoyed the delicious apples Mr Steiner left out for them each evening. Mr Steiner simply could not understand how Chester had ended up splatting onto his balcony like so much soggy laundry, and was my father able to shed any light on this unspeakable incident?

My father absorbed all of this information without a word. Then when it was clear that Mr Steiner had finished, he spoke.

“Hiz falling down,” he rumbled and closed the door in our neighbour’s face.

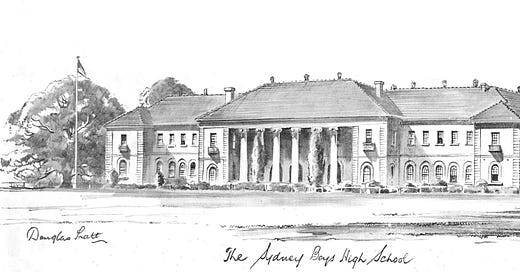

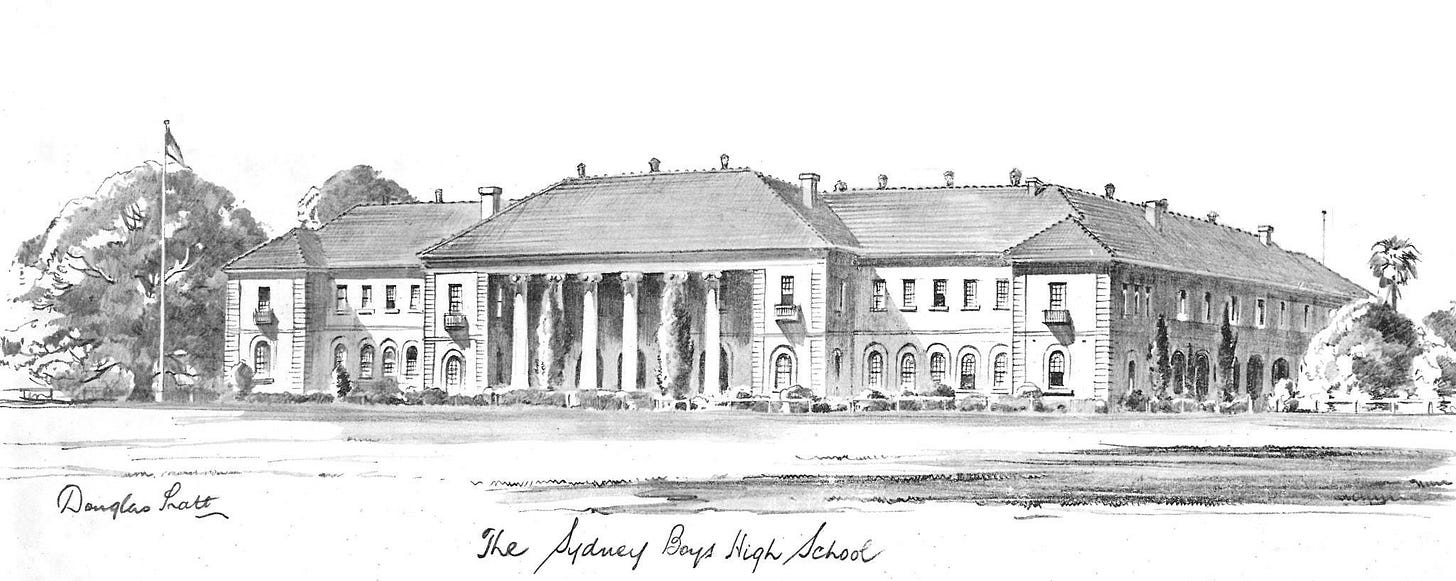

It was an altogether auspicious start to both my new living arrangements and my summer school holidays, at the end of which I would be attending Sydney Boys High School (founded in 1883) – a most prestigious educational facility situated on the edge of the vast Moore Park, and within spitting distance of the stunning and even vaster Centennial Park, the Royal Sydney Showground, and Sydney Cricket Ground. In the pamphlet we were sent the school boasted several football fields, a gymnasium, a glorious sporting history, and a faculty apparently entirely made up of black-robed, grim-faced wizards, if the photos were anything to go by.

But that was six-weeks away.

Two weeks later I must have been the first schoolkid in the history of the world to wish the holidays would end and school would begin. I was literally out of my mind with ennui, boredom, and loneliness. My only distraction was the pool and a burgeoning interest in rock music brought to me through the tiny tinny speaker of a small blue transistor radio that went everywhere with me.

But it’s not like there was anywhere much for us to go. The block of flats I lived in was on the vertiginously steep Stanley Street, which ran directly off the very busy Edgecliff Road, which I was forbidden to cross under pain of death, so I was pretty much constrained to roaming within a block or two of the flats I lived in. On foot, no less, since the pushbike my very handy father had made for me from scrap discarded at various tips, had been left behind in the move.

I was also somewhat unsupervised at times – my parents relying on a kind of rotating care-system as they shared me with their work obligations.

My mother was working as a toilet cleaner at Sydney’s Kingsford Smith Airport, which she rightly viewed as a step up from working as the toilet cleaner at the notorious Callan Park Mental Hospital. Her shift started at four am and she didn’t usually get home until about three in the afternoon, and sometimes longer if there was overtime involved. My father started work at 10pm each evening, returned home each morning about seven, bummed around the flat, or dug around in the engine bay of his car, and was asleep just after lunch. And while he was sleeping, I was pretty much on my own to do as I pleased.

If I was hungry, I would open the fridge and eat. Or I would walk down the hall to my aunt’s music-filled flat and she would feed me, while a vast assortment of beautiful Russian songs aided my digestion. She worked on the weekends as a barmaid at Sydney’s famous Wentworth Hotel and was consequently home during the week. And she could always be relied upon to flick me fifty cents to go and buy an ice cream or a can of drink. Sadly, unlike my milk bar in Glebe, my new milk bar did not have a pinball machine, so I could not while away the summer hours immersed in its joyous jangling and flashing.

I had splashed myself into a kind of itchy-skinned insanity in the pool and had spent so much time in its over-chlorinated depths my hair was tinged with green in bright sunlight and the edges of my fingernails and toenails were scabby with mild chemical burns.

And somehow, I was the only kid in the block of flats and seemingly, the only child for several blocks in any direction.

Glebe, where I had moved from, was noisy and teeming with kids. The streets echoed with the yells, shrieks and laughter of children, occasionally interrupted by a booming adult voice yelling instructions at its braying offspring and always underscored by the barking of dogs, faint music, and the barely audible susurrus of the nearby Broadway traffic. The thump of a kicked ball, the harsh metallic scratching of a billy cart being fired down a hill, and the flat rubbery crunk of an air rifle nailing a screeching cat was the soundtrack of my summers in Glebe.

Woollaraha was a noiseless tomb by comparison. The only people I saw were old people limping along with walking sticks or shuffling behind two-wheeled, vinyl-covered shopping trolleys – kind of like a small trunk with handles at one end and pram wheels at the other, and which were simply ubiquitous in that part of Sydney.

Where were all the kids? I wondered. There were certainly none living in the flats. And there were none playing in the streets anywhere near me. I was the only one who ever used the pool. My father swearing at the various mechanical issues he would discover in his car’s engine bay was the only noise I would ever hear in the courtyard below the block of flats. Sure, people (mostly elderly) came and went, but they made virtually no noise in the hallways and once they closed their front doors, it was as if they had winked out of existence.

Is this the suburb where people came to die quietly? Were they all zoned out on prescription chemicals? Were they vampires of some kind?

I had no idea, but it bothered me more and more as the summer wore on.

I used to spend hours sitting under some bushes across the street from my block of flats, sheltering from the summer sun with my back up against the warm bricks of someone’s front fence. The only thing moving was the heat haze coming off the bitumen and my foot tapping in time to music as brilliant as Deep Purple’s Black Knight, Janis Joplin’s take on Me and Bobbie McGee, and Credence Clearwater Revival’s Have You Ever Seen The Rain, or as catchily lame as Tony Orlando and Dawn’s Knock Three Times or Blame It On The Pony Express, by Johnny Johnson and The Bandwagon.

This music ensured my transistor radio was locked onto radio station 2SM, which was just starting to hit its straps as the pre-eminent music-provider for teenagers in Sydney with DJs like Ian McRae and Ron E Sparx.

And so my last pre-high school summer dragged on and on and on, until about a week before school was to commence, when mum announced that we would be going to the Grace Brothers department store at the nearby Bondi Junction shopping district to buy my school uniform.

My stomach lurched. I had managed to push the whole impending high school advent to some dark rock’n’roll-free corner of my brain, but mum’s declaration brought it front and centre.

The pamphlet Sydney Boys High had sent us after I was enrolled was quite explicit and pitiless in its uniform requirements. Clearly, the school took this whole uniform issue quite seriously and my mother wouldn’t be my mother if she didn’t take them seriously as well. Like all immigrants, she was overawed by officialdom and complied without question to all sorts of written edicts on official-looking letterheads.

Grace Brothers (or Gretz Bruddez as my mum called the retailer) was the only familiar aspect of this whole uniform-buying affair. In Glebe, we happened to live directly behind the huge department store, and my family were frequent visitors to this Aladdin’s Cave of consumerism. The Bondi Junction store was much smaller, but it still offered a dedicated school uniform section, which is where Mum and I went one sunny morning, clutching a list of quite precise and exhaustive sartorial requirements from my new high school.

I was not to attend Sydney Boys High unless I possessed four shirts (two long-sleeved and two short-sleeved), two pairs of grey pants (one short and one long), four pairs of socks (long and short), a jumper, a blazer, a sports uniform that consisted of two blue T-shirts with the school crest on them and two pairs of shorts, likewise adorned with the school crest. And a tie – an object that filled me with stomach-lurching dread. I was eleven years old, for pity’s sake. I had as much business wearing a tie as a moose had need of pants. My only experience with ties were fetching my father the pre-knotted items he only wore on special occasions and high holy days.

I was wall-eyed with anguish over having to knot this thing around my neck every day.

My mother appeared entirely unconcerned by my angst. She was too busy beaming with pride as the salesman fussed over me, ensuring each of these items vaguely fit, while greasily assuring my mum I would continue to grow and would, as time went by, fill out what I viewed to be entirely ridiculous spaces inside my new clothes.

When I shrugged on the heavy, scratchy brown wool blazer, I felt like he’d wrapped me in a sail. I looked like a slapstick sight gag.

“He looks very scholarly,” the salesman said, actually brushing imaginary lint from my padded shoulders like I’d seen people do in the movies.

Mum of course had no idea what the word “scholarly” meant, and I wasn’t entirely sure myself, but there were tears in her eyes as she smiled at me. She was very clearly consumed with pride.

That smile faded immediately she was presented with the bill for all these clothes. From memory, outfitting me for high school cost my family almost two weeks of combined parental wages – the wretched blazer alone accounted for a quarter of that cost.

Mum’s cleaning gig along with dad’s never-ending night-shift as a printer’s hand at Alexandria, and the fact we were living at the big end of town in Woollarah, meant that having too much money was never going to trouble us overly much.

That night, while dad and I ate dinner, mum ironed all the stuff that needed ironing and told my father he needed to teach me how to tie my tie.

“Bloody styoopit,” my father declared between mouthfuls of soup.

I was hoping he wasn’t referring to me.

“You must teachink,” my mother insisted, the iron hissing in her hand.

They had taken to practicing their English over dinner, the only meal when all three of us were present thanks to their work commitments. And while mum rarely ate with us (custom dictated that she served us food and only ate when it was all served), she was always present.

After dinner, I discovered that my father’s teaching skills when it came to tying a tie were somewhat lacking. He had very large hands, and I could just not see what they were up to around his neck with that accursed tie. No matter how I tried to get it, and no matter how many times he told me: “Not layk det! Layk dis! Layk dis!” while poking at the jumble of material at my neck with a meaty finger, I just could not get it.

I went to bed exasperated and affronted.

At four am I sat bolt upright in bed. The house was empty. Mum had just left for work and dad had been at work since 10pm and wasn’t due back until about seven. It was just me. Just me and the tie I now suddenly somehow “knew” how to tie. I grabbed it on my way to the bathroom, flicked on the light, stood in front of the mirror and tied an almost perfect Windsor knot as if I had been tying them forever. Then I did a little victory dance and went back to bed. Clearly, my teachers were right. I was gifted. Sure, I may have been a little slow out of the blocks, but it was obvious my subconscious mind would work at a problem until it had been solved. I obviously had no fucken idea about algebra at this stage in my life, and the mewling imbecile it would reduce me to in a few short weeks, but I was feeling very good about myself that early morning.

I was feeling sick to my stomach a week later when dad drove me to my first day of high school. My uniform – and I was wearing most of it, including the thick woollen blazer, because the pamphlet said: “Students will present themselves in full school uniform on the first day of school” and to my mother the term “full school uniform” meant just that. All of it. And summer be buggered. She had even insisted I put the jumper on under the blazer, but my father over-ruled her, fearing I may collapse from heat-stroke. Nonetheless, she insisted I take the jumper with me just in case.

But sweating like a bison in rut was the least of my problems. My first day at high school was right on course in its downward spiral.

To my cringing shame, my father actually drove his creaking old 1963 XL Falcon into the school playground. Functionally illiterate in English and never one for paying much attention to signs, the old man simply drove past all the “Parking” signs the school had ensured were prominently displayed for concerned parents dropping off their kids, and turned into the next gate, which led directly into the playground – which was full of kids and a few teachers, all of whom were looking at us. Whereupon he lurched to a stop. Then he reached over, grabbed me by the shoulder dragged me over to his side of the car and kissed me on the face.

“Bi goot boy,” he intoned.

I pretty much fell out of the car as one of the teachers came rushing over to the driver’s window.

“You can’t drive here, sir!” he spluttered at my father, who was busily engaged in persuading the old Ford’s clutch and gearbox to co-operate and offer up reverse gear.

“Sir!” the teacher insisted, leaning into the window.

“Vot?” my father snapped at him.

“You cannot drive here!” the teacher reiterated. “This is a playground!”

“I not drivink,”my father stated, finally finding reverse with a graunch of gears. “I goink.”

I watched him reverse back the way we’d just come because I could not bear to look at the playground full of my new school mates, some of whom I could hear were already reduced to fits of laughter and derision.

“What is your name?” the teacher asked me.

“Boris Mihailovic,” I muttered.

“Muhchuklavchuk,” he hacked, like he had something unpleasant and spiky in his throat. “Go to the hall. All First Formers are to go to the hall.”

Then he walked off, leaving me wondering a) where the hall was, and b) how I had managed to mispronounce my own surname in such a way.

But I could not stand where I was all day, sweating into the crack of my arse and staring at the ground. I shouldered my bag, and started walking further into the playground, noting that I was the only kid wearing a blazer, and wondering when the “welcoming” would start.

The “welcoming” was, of course, a type of hazing that greeted First Formers in every high school in Australia at that time. It was the stuff of legend. My final year in Glebe Primary was full of tales from other kids about how their brothers had been up-ended into toilets, or had their pants removed, or their undies savagely pulled upwards into the cleft of their screaming buttocks – hell, the list of horrors inflicted upon the hapless First Formers by older students went on and on. Everything from being forced to eat dog shit on a stick to licking the shoe-soles of the Fourth Formers, was covered in teeth-clenching detail. So as I made my way into the school I felt much like a small gazelle must feel walking into a herd of giant lip-licking lions. I was light-reflective with sweat. It was leeching out of me like the tears of a clown – whom I would have resembled, given my entrance and outfit. The combination of mindless fear, polyester, wool, a Serbian father, and shitty horn-rimmed glasses on a summer’s day is hard to beat.

And then the wait was over.

The first older kid who was in arm’s reach of me grabbed my tie and pulled it so hard I had to cut the furiously knotted bastard off with a pair of scissors when I got home that afternoon. Then someone tripped me. Then someone else took my bag and emptied its contents onto the playground. I didn’t mind seeing my salami sandwiches being kicked out of sight since I would probably not live until lunchtime anyway, but I was concerned my new woollen jumper was being employed as the rope in an impromptu tug-of-war.

I could feel the tears beginning to well in my eyes, but I knew that to cry would only make everything much worse. Even at that early age, I knew that fear only fed the predators. Perhaps the character-building I’d received in Glebe Primary School at the hands of Eddie Bonbridge and his mates had toughened me a little after all.

The sleeves of my jumper were reaching truly epic lengths when a very tall student with a Prefect badge on his senior tie stepped in.

Prefects were a bizarre and anachronistic legacy from the English school system which provided that certain senior students, selected by the teaching faculty, would receive badges and be able to…well, boss other students around. Kind of like de facto teachers, or Ukrainian prison guards in Nazi extermination camps, but without the clubs. Four years later, in my second high school, the Prefect system and I would clash in a way that would see it removed from that high school and me suspended for a week. But that morning that Prefect was my saviour.

“That’s enough, you pricks,” he barked, snatching my jumper off the two kids who’d been seeing if it could be stretched across the playground. He also picked up my bag, my now empty lunch box, and the scuffed and empty new exercise books I had also been compelled to buy prior to attending the school.

“You okay?” he asked, handing me the items.

I nodded wordlessly.

“The hall’s just around there,” he pointed. “Don’t worry about those dickheads. But you’re gonna get a bit of a shit-stir for a few days. And you don’t have to wear the blazer, you know. That might help a bit.”

I nodded again, repacked my shit into my bag, then I took off my blazer, pushed it into the bag as well and went to the hall.

I lined up with the “Surnames L-Z” and awaited my fate.

The differences between high school and primary school were so vast and so immediately obvious my head was swimming with the implications.

For starters, the school itself was immense, built on a scale that made my spine fizz. It had quadrangles and science blocks and a gymnasium and a hall and a music wing and an administration block where the headmaster had his throne room and which was lined with the busts of former headmasters. Here, the walls were hung with massive lacquered wooden boards, upon which were scribed in gold the names of various students who had excelled at studenting, Prefecting, School Captaining, and various sports. As juniors, we were not allowed into this block, but during the first few weeks, we were given turns at being class monitors – which was a fancy name for scurrying servants, who would run errands for the teachers and thus learn the layout of the school. Or presumably perish.

The school also shared a beautiful grassed and tree-filled playground with Sydney Girls High, and the senior students were permitted to mingle there during recess and lunch. The juniors, however, were to remain within their designated bitumen playground at all times. This was clearly so that our immature vileness would not offend the elaborate and nuanced teenage mating rituals that occurred there at lunchtime. This was quite a change from Glebe Primary, which would rope off a section of street for us to play in each recess and lunch, and where the girls were all considered to have a surfeit of germs and thus to be avoided at all costs.

Secondly, there was the whole food chain issue. I had left the primary school at the top of the pecking order in terms of seniority. Certainly, I did not breathe the rarefied air of supremacy the bullies and the sports stars inhaled, but I had done well academically and that aside, I had been in sixth grade, which was to hell and gone better than being in any of the lesser grades. But now I was in First Form and at the very bottom of the food chain. I was physically smaller than most of the school, as were my fellow First Formers, with the exception of Paul Thurston, who was twice as big as the rest of us and had probably been shaving and having sex with hookers for the last year. The Sixth Formers were, to my young eyes, the size of giant adults, as were the Fifth Formers. Happily, most of these titans were pre-occupied with impending exams and having sex with the girls at the neighbouring school. And most of them were so tall they didn’t even see us First Formers scurrying out of their way. The Fourth Formers were only slightly smaller, but made of for their lack of size by being rowdier and more aggressive, while the Third Formers and Second Formers made it their life’s work to ensure that we First Formers spent our days in misery, dread, and various forms of pathetic supplication each time our possessions were burned, thrown into the toilet, or lobbed into passing traffic.

The sour sense of fear was quite palpable as we quietly milled in the hall where our names were marked off, given timetables, and told which classes would be our Home Room classes, and where within the school they could be found. But there was also a sense of great excitement. This was indeed a very great adventure for us all. The commencement of something important; the true nature of which was yet to be determined.

From where I was in the middle of the hall, I could see that many of the students knew each other from the primary schools they had attended together in the area. I knew no-one, and consequently stood around trying not to make eye-contact with anyone in case they punched me in the face. Surreptitiously glancing around, I was disturbed to discover I was one of the few wog kids enrolled at the school. The surrounding areas, from where the students were mostly drawn, were quite obviously not overflowing with post-war immigrants. They were instead the domain of upper middle-class Australians and a fair few Jewish kids – who were certainly not at all wog-like or en-dagoed like the kids at Glebe.

But it wasn’t all bad. For starters, my uniform fit me just as badly as it did many of the other kids. So I wasn’t the only one who must have felt like a circus marmoset dressed in outsized human clothing. I had no explanation for those smarmy, strutting little shits upon whom the uniform sat as if tailored to their bodies, but it was heartening to see that my mother was not the only one who understood “full school uniform is to be worn at all times” to mean “make sure your kid is wearing everything you bought for him at Gretz Bruddez on his first day of school”.

Then there was the drink machine outside the hall – an altogether magical contraption which enamoured me on the first day and had me in thrall to its smashed-ice-and-fizzy-sugar-syrup the whole time I went to Sydney Boys High. For a mere ten cents, this miracle of soft-drink science would vomit forth a paper cup and automatically proceed to fill it with a dollop of crushed ice and your choice of either cola, lemonade, or red-stuff, which tasted vaguely of strawberries made from cough mixture. It was like something out of the TV show Lost in Space and the first soft drink-dispensing machine I had ever beheld. And the fact it was in my school filled me with awe and pride in equal measure. I quickly became a regular visitor and was always filled with vast disappointment when it would not work – which was actually quite often.

The third, and to this day, most positive facet of my new school was the appropriately-named Miss Peachy, my Home Room teacher – and one of the most stunning red-headed women I have ever laid eyes upon. The entire class of snotty pre-pubescent brutes whose names she marked off her roll each morning were utterly bewitched by her, and her boy-killing arsenal of big tits, skin-tight tops, and hip-hugging pencil skirts. She was one of the few teachers at the school not cut from the mould of the black-robed Masters, whose iron-stern visages and caches of punishment-canes ruled our school days.

But apart from giving us all painful and lengthy erections during roll-call, Miss Peachy also taught English, Ancient Greek, and Latin. All subjects sadly missing from today’s enlightened high school curricula.

PART B TO COME...